I posted some new software on github here.

The field-emission scanning electron microscope we use in our lab is a commercial instrument, primarily made for industry to do things like failure analysis of mechanical parts. It is not designed for cosmochemistry, but the best instruments are flexible enough to allow us to do what we need to do efficiently. Our microscope allows for this through a Python-powered scripting interface and easy-to-automate XML files.

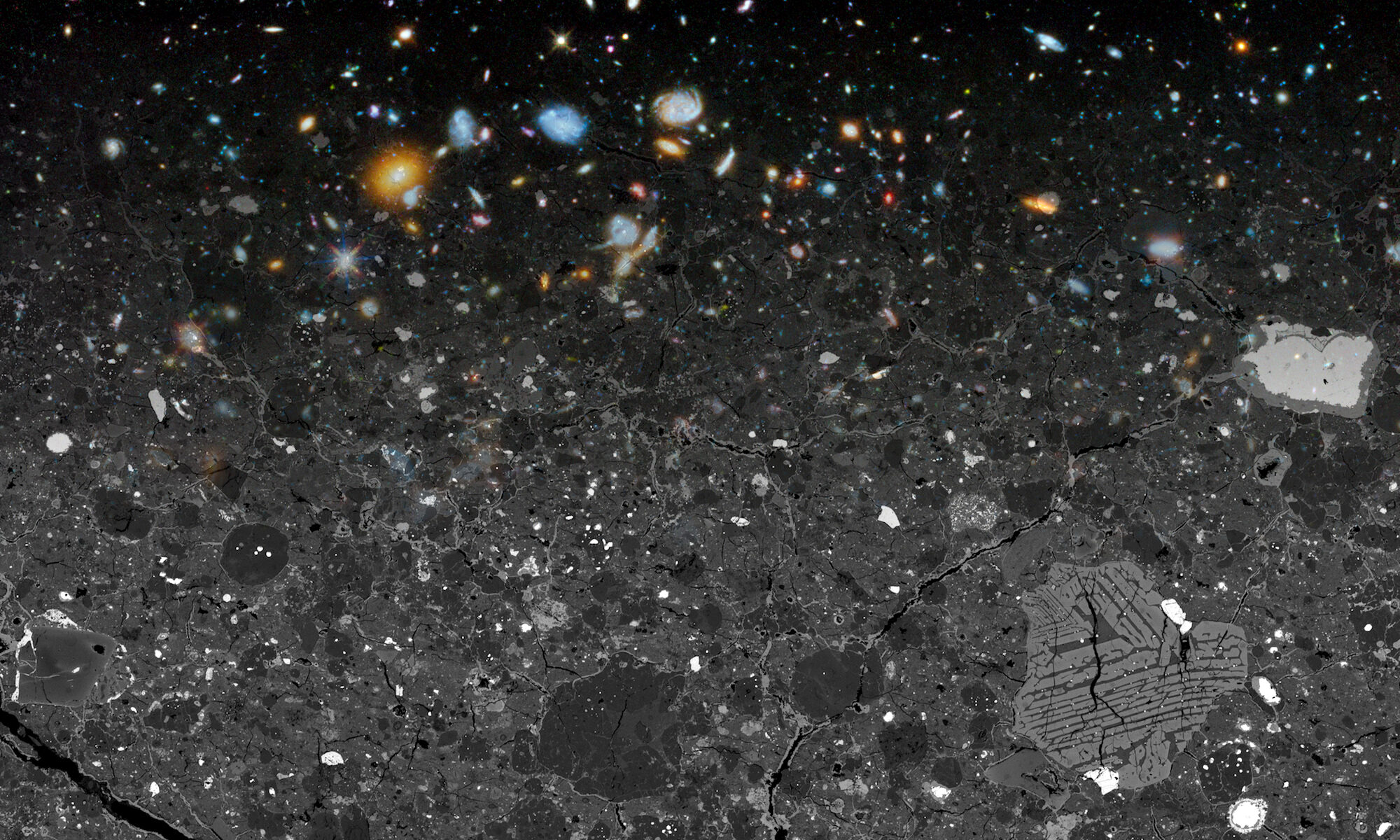

In our research we’re frequently looking for rare objects in a relatively large sample — such as hypervelocity impact craters on a metallic surface. So we have a need to acquire electron images over a large surface area that is tilted (or otherwise non-flat) on scales much larger than the depth-of-field of the electron image (typically ten micrometers). Our electron microscope can do autofocus, but this is slow and unreliable. The above code acquires a coarse topographic map and then fits a surface to this map from which it acquires high resolution images. Now we are able to scan centimeter-sized samples to look for micrometer-size features in a reasonable time! The company that makes the microscope certainly can’t foresee all of the uses we have for it, but we have the ability to control the microscope at a very basic level. And since we know how to do math and write code, anything is possible!